Khaladka ugu weyn ee amniga adduunka qadiimiga ah: Casharrada amniga ee Dooxada Boqorrada

Mahadsanid fasax dheer oo sanadle ah oo Mastercard ay bixiso (waxaan helnay 25 maalmo!) I took a two week trip to Egypt earlier this month to visit a place I have always wanted to see: the burial tombs of the ancient pharaohs in the Valley of the Kings. As a security engineer, I could not help looking at these tombs as an ancient security program and as a case study on how defenses can fail over time.

Ancient Egypt left behind more artifacts than most other ancient cultures. One reason is that the Egyptians, especially their kings, were deeply focused on death and the afterlife with their physical bodies. They believed the body must be preserved (mummified) so the king could continue his journey after death and become a god! Because Egyptians invested so much in funerary goods and mummification, many objects survived at least until tomb raiders found some of them.

A brief look at the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62) which was discovered in the early 20th century, shows what might have been placed in other royal tombs. It was one of the few royal tombs not fully looted in ancient times. It contained hundreds of kilograms of gold and many other treasures from over 3,300 years ago.

Golden Throne of Tutankhamun was found in his burial chamber by archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922

From obvious pyramids to hidden tombs

In the Old and Middle Kingdoms, kings built pyramids as burial placements. These monuments were easy to see, which also made them easy to target. Even though they used blocking stones and other tricks, many were robbed. Later, in the New Kingdom (about 3,500 years ago) pharaohs moved to a new model: security by obscurity. They saw what happened to the pyramids of their predecessors, so they chose a remote valley on the west bank of the Nile, near today’s Luxor, and dug hidden tombs into the rock. They built and isolated a workmen’s village, Deir el‑Medina, to keep the location and details secret. For about 500 years, this village produced the tombs of new pharaohs.

The Pyramid of Djoser is considered the first pyramid ever built approximately 4,700 years ago.

These tombs were essential. The dead needed their mummified body, objects, offerings, and guides like the Book of the Dead to reach Osiris and live in the afterlife. If a tomb was robbed, it was not only a material loss but it was a spiritual failure.

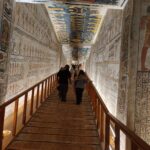

What I saw on my visit

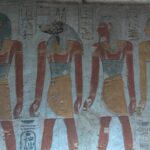

I visited almost all tombs open to the public in the vally of the kings, valley of the queen, and deir-el Madinah. One of the interesting observation is that you can see different risk choices by different kings. Some placed their tombs in more accessible locations, betting on internal complexity and decoration. Others, like Thutmose III, chose harder, more hidden positions. But in the end, almost all of these tombs were found and robbed during later periods of instability by motivated attackers. This means that even the smarter and more risk averse kings also failed in their security designs. Here is my take on why the defenses failed and how it could have been better.

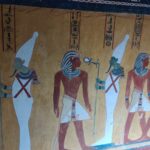

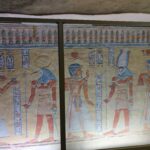

Burial chamber of Ramses the third in my background.

Why the defenses failed

- Security by obscurity was the main control. Hidden entrances, sealed doors, and a remote valley helped, but they were not enough for a defense that needed to last thousands of years.

- Time favored attackers (I always say this one to my clients!). Over centuries, secrecy leaks. Rock shifts. Political crises come and go. Motivation stays high when treasure is involved.

- Limited defense in depth. Blocking stones and false corridors slowed attackers but did not stop tunneling or insider‑enabled bypass. The main defense was security by obscurity and no additional controls.

- Insider threat, late New Kingdom instability, inflation, and delayed rations (the strike at Deir el‑Medina) increased theft and bribery. Trial records mention stonemasons, smiths, necropolis police, and low ranking priests involved in robberies.

- Single points of failure with a trusted community. Too much knowledge and access sat with one small, trusted community. Once secrecy failed there, the whole system failed.

- No continuous monitoring or incident response was in place (very difficult to put it in place for thousands of years and more!). Painted snakes and divine guardians were symbolic, not real controls. (They had many of them on the walls and around coffins!) There were seals, but there was no sustained monitoring, patrols, or effective response over the long term.

Common security mistakes by the Pharaohs

- Controls did not match asset value. If you bury hundreds of kilograms of gold with the king, you invite extreme, persistent attacks. The defense did not match that high value.

- Over reliance on secrecy. Obscurity helped at first, but there were few layered controls after secrecy was gone.

- No least privilege! Many workers in Deir el‑Medina had broad knowledge of plans, maps, and layouts. This enabled later robberies.

Weak access governance. Privileged access management did not exist in a modern sense. The same teams that built the tombs knew how to breach them.

How they could have improved

- Reduce attacker motivation (MOM framework: Success = motive + method + opportunity): They should not bury large amounts of gold with the body. Keep the body for the afterlife, but remove the main motive.

- If treasure must be buried, separate it from the mummy in independent, randomized chambers, far from the main burial, with anti‑tunneling features (rubble trenches, hard bedrock layers, decoy shafts).

- Add defense in depth: Multiple sealed compartments with different sealing methods and independent stone barriers.

- Physical anti‑tamper layers that make tunneling noisy, risky, and slow.

- Enforce least privilege of knowledge: Split design details so no single team knows the full layout. Rotate crews, compartmentalize tasks, and use need‑to‑know for locations of final burial chambers.

- Keep final chamber work to a very small, highly trusted team, then remove or relocate them.

- Deception: Multiple decoy chambers with convincing goods, placed early in the build so workers think the decoy is real. False burial events to create misleading oral history.

- Burial chamber of ramses the third in my background.

- Bent Pyramid

- King Djoser’s burial placement (circa ~4700 years ago)

- I went 89 meters down to reach the first burial chamber of the Bent pyramid

- King Thutmose III circa ~1500 BCE

- oppo_16

- The Pyramid of Djoser is considered the first pyramid ever built approximately 4,700 years ago.

- Golden Throne of Tutankhamun was found in his burial chamber by archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922

- A panoramic view of the great pyramid 1

- A panoramic view of the great pyramid 2

Post Disclaimer

The views, information, or opinions expressed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of his employer or the organizations with which he is affiliated.

Macluumaadka ku jira qoraalkan waxaa loogu talagalay ujeeddooyinka guud ee macluumaadka oo kaliya. Macluumaadka waxaa bixiyey Farhad Mofidi waxaana uu dadaalaa inuu macluumaadka ka dhigo mid hadda jira oo sax ah, laakiin ma sameeyo wax matalaad ama damaanad qaad ah oo nooc kasta ah, si cad ama si leexsan, ku saabsan dhamaystirka, saxnaanta, kalsoonida, ku habboonaanta ama helitaanka bogga internet-ka. Farhad ma sameeyo wax matalaad ama damaanad qaad ah. ama wax macluumaad ah, alaabooyin ama garaafyo la xiriira oo ku jira qoraal kasta oo loogu talagalay ujeedo kasta.

Sidoo kale, AI waxaa laga yaabaa in loo isticmaalo aalad si loogu bixiyo talooyin iyo in la hagaajiyo qaar ka mid ah waxyaabaha ama jumladaha. Fikradaha, aragtiyada, moodooyinka, iyo alaabooyinka ugu dambeeya waa kuwa asalka ah oo bini'aadamka ay sameeyeen qoraaga.